On August 1, 1966, rioting rocked the Near-Northside as Paul Young began his duties as Special Agent in Charge of the Omaha Federal Bureau of Investigation office, his first command. Young could not foresee the awful deed he would commit four years later, allowing a policeman’s killer to get away with murder. Omaha’s explosive racial problems dominated Young’s attention.

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, unhappy with President Lyndon Johnson over civil rights legislation, made it a practice of flooding the White House staff with every racial incident in the country that came to the attention of the FBI network of field offices. Hoover submitted a written report to the White House on events in Omaha during Young’s first day on the job.

“Approximately 50 Negro youths gathered in the Negro district of Omaha, Nebraska, during the early morning of July 31, 1966. The group became unruly and broke windows in several business establishments. Before any looting occurred, however, the Omaha Police Department arrived on the scene and arrested six individuals. The group was dispersed and order restored.”

“During the late evening of July 31, 1966, and early morning of August 1, 1966, Negro youths again took to similar activities. Seven stores were looted and at least four stores were the object of fire bombs. Fifty extra police officers were dispatched to the Negro area of Omaha where 17 individuals were arrested on suspicion of burglary and a crowd of about 150 individuals was dispersed. One Negro boy, aged 18, was struck by shotgun pellets as he left a liquor store that had been burglarized.”

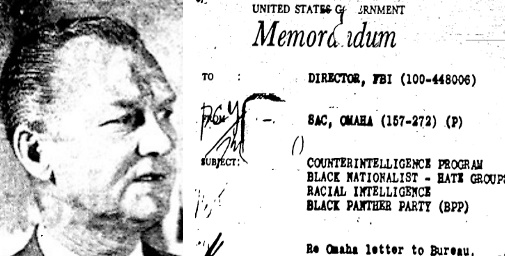

Young was summoned to Washington in March 1968, where a “Racial Conference” was convened at FBI headquarters. Led by George Moore from Racial Intelligence and William Sullivan from Domestic Intelligence, forty-one attending field office supervisors received counterintelligence directives from Hoover who warned: “Counterintelligence operations must be approved by the Bureau. Because of the nature of this program each operation must be designed to protect the Bureau’s interest so that there is no possibility of embarrassment to the Bureau.”

While Young was getting his marching orders from Hoover, rioting broke out in Omaha after protesters were beaten at a George Wallace rally. Hoover’s daily report to the White House described events in Omaha.

“Inspector Monroe Coleman, Omaha, Nebraska, Police Department, advised yesterday that as an aftermath of the appearance of former Alabama Governor George C. Wallace at a political rally…several incidents of violence by Negroes took place in Omaha. Among these were the vandalizing of a pawnshop…and the subsequent fatal shooting of a 16-year-old Negro boy by an off-duty police officer during an attempt by the young Negro to loot the pawnshop. Several assaults by Negroes against white persons also occurred after the former Governor Wallace rally and two of the white persons reportedly were seriously injured. Public buses were stoned by Negroes as they passed through Omaha’s north side and yesterday morning Negro students of several Omaha high schools broke windows in business establishments while on their way to school. The students later caused minor damage in the schools by setting fires in wastebaskets in the restrooms and by throwing rocks through the windows of the schools.”

Despite Hoover’s insistence that counterintelligence operations be conducted promptly, Young failed to offer a proposal under the Bureau’s clandestine COINTELPRO program. By December 1969, Hoover had grown tired of waiting. Just days after FBI-orchestrated raids against the Black Panthers in Chicago and Los Angeles, Hoover ordered Young to submit a plan for action.

“While the activities appear to be limited in the Omaha area, it does not necessarily follow that effective counterintelligence measures cannot be taken. As long as there are BPP activities, you should be giving consideration to that type of counterintelligence measure which would best disrupt existing activities. It would appear some type of counterintelligence aimed at disruption of the publication and distribution of their literature is in order. It is also assumed that of the eight to twelve members, one or two must surely be in a position of leadership. You should give consideration to counterintelligence measures directed against these leaders in an effort to weaken or destroy their positions. Bureau has noted you have not submitted any concrete counterintelligence proposals in recent months. Evaluate your approach to this program and insure that it is given the imaginative attention necessary to produce effective results. Handle promptly and submit your proposals to the Bureau for approval.”

Forced to submit written reports every two weeks on his progress against the National Committee to Combat Fascism, the Omaha affiliate of the national Black Panther Party, Young finally got his chance to satisfy Hoover’s demands in August 1970 when a policeman was murdered by a bomb in a vacant house.

Paul Young wasted no time to privately talk with Deputy Chief Glen Gates, who was in charge of the police while Chief Richard Anderson was out of town. According to a confidential FBI memorandum, Young and Gates discussed a piece of crucial evidence, the recorded voice captured by the 911 system of the anonymous caller who lured police. The search for truth was over.

Young set in motion a conspiracy to implicate the leadership of the National Committee to Combat Fascism in the bombing. Young wrote to Hoover, “Enclosed for the Laboratory is one copy of a tape recording obtained from the Omaha Police Department.”

“Deputy Chief [Gates] inquired into the possibility of voice analysis of the individual making the call by the FBI Laboratory. He was advised the matter would be considered and that if such analysis were made and if subsequent voice patterns were transmitted for comparison, such analysis would have to be strictly informal, as the FBI could not provide any testimony in the matter; also, only an oral report of the results of such examination would be made to the Police Department. [Gates] stated he understood these terms and stated the Police Department would be extremely appreciative of any assistance in this matter by the FBI and would not embarrass the FBI at a later date, but would use such information for lead purposes only.”

“It should be noted that the police community is extremely upset over this apparent racially motivated, vicious and unnecessary murder. In slightly over three months this division has experienced more than ten bombings, probably all but a few of them being racially motivated. Of these bombings, four were directed at police facilities with extensive damage.”

“Any assistance rendered along the lines mentioned above would greatly enhance the prestige of the FBI among law enforcement representatives in this area, and I thus strongly recommend that the request be favorably considered.”

Hoover agreed to squelch a laboratory report on the identity of the 911 caller to make a case against Edward Poindexter and David Rice [later Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa] who were leaders of the NCCF in Omaha.

In October 1970, Young became concerned that the FBI Laboratory might forget and issue a report on the 911 recording and wrote a memorandum to Hoover reminding that the 911 tape was not to be used.

“In a preliminary hearing held 9/28/70 in Municipal Court, Omaha, PEAK testified that he had made the telephone call to the Omaha PD telling them that a woman was screaming in a house at 2867 Ohio Street. Police Officer LARRY MINARD was subsequently killed when a bobby trap suitcase exploded as he, with other officers, answered this call.”

“Assistant COP GLENN GATES, Omaha PD, advised that he feels that any use of tapes of this call might be prejudicial to the police murder trial against two accomplices of PEAK and, therefore, has advised that he wishes no use of this tape until after the murder trials of PEAK and the two accomplices has been completed.”

“UACB [Until Authorized to Contrary by Bureau], no further efforts are being made at this time to secure additional tape recordings of the original telephone call.”

The defense was never offered a copy of the 911 recording during pre-trial discovery and the jury that convicted the two Panther leaders never heard the voice of a killer. No analysis was conducted to determine the identity of the anonymous caller.

Poindexter and Rice were convicted in April 1971 after a controversial two-week trial. David Rice died at the maximum-security Nebraska State Penitentiary in March 2016 serving a life without parole sentence. Paul Young was rewarded for his role in the case with a promotion to head the FBI office in Kansas City. Ed Poindexter is in his forty-eighth year of imprisonment and continues to proclaim his innocence.

This article contains excerpts from the new book FRAMED: J. Edgar Hoover, COINTELPRO & the Omaha Two story. The book is available in print from Amazon and also in ebook format. Portions may be read online free at NorthOmahaHistory.com. Patrons of the Omaha Public Library also have access to the book.

Reblogged this on Moorbey'z Blog.

LikeLike