The August 17, 1970 bombing murder of Patrolman Larry Minard prompted a request from Special Agent in Charge Paul Young of the Federal Bureau of Investigation office in Omaha for assistance in the case. Young’s request was unusual in that no written report was to by made the FBI Laboratory to help solve the crime.

A secret memorandum to lab chief Ivan Willard Conrad outlined a covert plan to withhold a report on the identity of the unknown 911 caller who lured police into a deadly trap. Operating under directives from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover under the clandestine COINTELPRO program, Young moved quickly to place the blame for the bombing on leaders Edward Poindexter and David Rice of Omaha’s affiliate chapter of the Black Panther Party called the National Committee to Combat Fascism.

Assistant to Hoover and third in command of the Bureau,William Sullivan was on the memorandum distribution list and initialed the document indicating his approval of the conspiracy to withhold a lab report on the 911 caller’s identity.

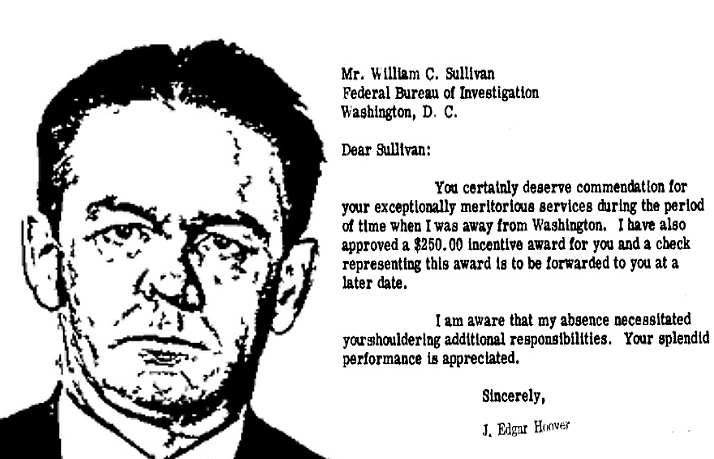

Three days later back from vacation, Hoover gave Sullivan an unexpected $250 “incentive award” for the time Hoover was gone. Sullivan’s duties included going along with the plan to withhold a FBI Laboratory report on the identity of a policeman’s killer.

Hoover wrote, “You certainly deserve commendation for your exceptionally meritorious services during the period of time when I was away from Washington.”

“I am aware that my absence necessitated your shouldering additional responsibilities. Your splendid performance is appreciated.”

A second memorandum to Ivan Conrad at the FBI Laboratory about the Minard murder reviewed developments in the crime investigation and reaffirmed the earlier request to not issue a laboratory report. William Sullivan’s initials are beside his name indicating his approval. The war on the Black Panthers was a priority for Sullivan and he stayed informed, following counterintelligence actions and developments closely.

In October 1970, Sullivan spoke to a convention of United Press International editors and reporters in Williamsburg, Virginia. When asked about communist responsibility for racial unrest Sullivan admitted that no evidence existed of communist instigation of any of the riots that erupted in cities around the nation over the summer and instead blamed extremists.

“The vanguard of black extremism today is the Black Panther Party with its demonstrated proclivity for violence. The party was founded in 1966 ostensibly as a self-defense group against police officers. It has, however, been constantly on the offensive in keeping with its battle cry of “off the pigs”—Panther jargon for “kill the police”. According to Panther thinking, the police are the first target in the program for “liberation” of the black community and the violent destruction of white America.”

The speech would prove to be the last of Sullivan’s FBI career. Hoover was furious with Sullivan and said the speech threatened the Bureau’s budget by elimination of the communist threat.

Sullivan’s speech included a denial of counterintelligence actions against the Black Panthers and the only public FBI mention of the bombing in Omaha. Sullivan didn’t have all of his facts correct, he was wrong on the date and number arrested.

“On August 12, 1970, an Omaha, Nebraska, police officer was literally blasted to death by an explosive device planted in a suitcase in an abandoned residence. The officer had been summoned by an anonymous telephone complaint that a woman was being beaten there. An individual with Panther associations had been charged with this crime.”

Anti-war protests filled Washington in May 1971 with demonstrators. Sullivan and an unidentified “Security Coordinating Supervisor” took to the streets to see what was going on. The supervisor later prepared an affidavit on Sullivan’s tour.

“One of the areas we visited was Dupont Circle….I observed a young male demonstrator on the sidewalk to the right of the car and standing about 15 feet from the car. He jeered at us and made noises which gave me the impression he felt we were police officers. I raised my camera in an attempt to secure a photograph of the man through the windshield of the car, during which time he continued to jeer and moved toward our vehicle. Mr. Sullivan removed a canister of mace from his pocket, rolled the window down and sprayed mace at the man who was then about 6 feet from the car. I did not secure a photograph; the signal light changed and we immediately drove out of the area.”

The next day Sullivan got another taste of action when he was surrounded by protesters outside the Justice Department building as he surveyed the scene of an angry protest. FBI agents arrested a man for writing on the walls of the building with red paint. As demonstrators moved toward the arrest, Sullivan found himself alone in a hostile crowd. An agent later provided a first-hand report. “The crowd surged forward and someone yelled that Assistant Director Sullivan was still out there. I saw Sullivan standing alone about four feet from the gate. The crowd was yelling at him and the obscenities continued. Suddenly his foot flew out as if to kick at a demonstrator.”

“I did not see him make contact with his foot. Then to defend himself, I next saw Sullivan waving a blackjack in his right hand. He was still about four feet from the gate. The two agents rushed out and forced him back inside the entranceway. The crowd continued to throw objects and spit at all of us.”

Relations between Hoover and Sullivan further deteriorated. A visit to Hoover’s inner office turned into a two and a half hour shouting match. Hoover berated Sullivan for a litany of errors and faults. Sullivan told Hoover that he should retire.

Hoover then formally requested that Sullivan apply for retirement immediately and take accumulated leave. Sullivan had lost the struggle with Hoover for control of the FBI. “It has been apparent to me that your views concerning my administration and policies in the Bureau do not meet with your approval or satisfaction, and thus has brought about a situation which, though I regret, is intolerable for the best functioning of the Bureau.”

Hoover’s last encounter with Sullivan resulted in another hollering session. Hoover shouted at Sullivan. Sullivan shouted back. The heated exchange between the two men drove Hoover to write again to Sullivan about forced retirement. “I deeply regret the occasion to take action such as this after so many years of close association, but I believe it is necessary in the public interest. Your recently demonstrated and continuing unwillingness to reconcile yourself to, and officially accept, final administrative decision on problems concerning which you and other Bureau officials so often present me with a variety of conflicting views has resulted in an incompatibility so fundamental that it is detrimental to the harmonious and efficient performance of our public duties.”

Sullivan took to the road on a speaking tour about his days with the Bureau. Sullivan’s account of J. Edgar Hoover’s mental decline made the front-page of the Boston Globe in an article entitled “Ex-aide Bares Hoover’s Erratic Last Years.” Sullivan called Hoover “raving mad.” According to Sullivan, Hoover was “extremely erratic” and would go into rages filled with with wild talk. The unstable episodes increased in frequency during the three years before Hoover’s death in 1972.

A seemingly reformed Sullivan submitted written comments to the Roscoe Pound American Trial Lawyers Foundation proposing a three-year moratorium on government eavesdropping.

“The FBI as it is now structured is a potential threat to our civil liberties, recent events indicate this…..It would help greatly in removing the FBI from politics and politics from the FBI…This would be a tremendous accomplishment for the good of the country.”

“The weaknesses of the FBI have always been the leadership in Washington, of which I was a part for 15 years. I accept my share of blame for its serious shortcomings.”

Sullivan was being untruthful with the lawyers group. Sullivan accepted no blame for COINTELPRO crimes and did not reveal his control of illegal counterintelligence actions. Sullivan did not reveal he approved a conspiracy to let an Omaha policeman’s killer get away with murder.

On a chilly November day in 1977, Sullivan arose before dawn at his Sugar Hill, New Hampshire home and set out on an early-morning walk in the woods. Across a field, a young hunter, Robert Daniels, Jr., son of a state trooper, picked up movement in his rifle scope and fired.

William Sullivan died where he fell, in a pool of his own blood. FBI Disrector Clarence Kelley received a teletype message about Sullivan’s death from the Boston field office. FBI agents knew of the shooting for an hour and a half before the widow was told by a former special agent and the local police chief, a friend of Sullivan.

The House Assassinations Committee wasted no time in seeking the papers and files of Sullivan. Committee chief investigator, Clifford Fenton, Jr. showed up at Sullivan’s house with a subpoena for records. Sullivan’s widow had left for the funeral in Massachusetts and was not home. Sugar Hill Police Chief Gary Young denied Fenton access to the residence and publicly criticized the attempt to get information ending the Committee effort. Sullivan had been slated to testify to the Assassinations Committee.

Attorney William Kunstler charged that William Sullivan was murdered to keep him from talking about what he knew about the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.

“There isn’t the slightest doubt. I think Mr. Sullivan’s death will present a shocking picture of a cover-up greater in scope than Watergate.” Kunstler said that Sullivan was poised to “blow the whistle” on the slayings of the two black leaders.

Kunstler followed with a formal request to Attorney General Griffin Bell to investigate the death of Sullivan. “I call to your attention the fact that there was ample motive on the part of scores of individuals to desire Mr. Sullivan’s death. Among other things, it was Mr. Sullivan who apparently revealed the inner workings of COINTELPRO, the acronym for the FBI’s covert action program against domestic groups.”

“I call upon you, with all the force I can muster, to order at once the investigation sought by this communication. The recent history of this country has revealed that cover-ups of crime are not isolated or aberrational events.”

The Justice Department responded to Kunstler that there would be no investigation into the death of Sullivan. “The person responsible for the shooting has acknowledged it and the physical evidence substantiates his account.”

The two Black Panther leaders framed by Sullivan and others for the Omaha bombing, Poindexter and Rice (later Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa), were convicted in a controversial 1971 trial ten days before COINTELPRO was officially terminated. The jury never heard the killer’s voice on the recording that had been sent to the FBI Laboratory and no analysis of the 911 tape was made.

Mondo died at the maximum-security Nebraska State Penitentiary in March 2016. Poindexter remains imprisoned serving his life without parole sentence, forty eight years later, where he continues to proclaim his innocence.

The article is excerpted from my new book, FRAMED: J. Edgar Hoover, COINTELPRO & the Omaha Two story, in print edition at Amazon and in ebook. Portions of the book may be read free online at NorthOmahaHistory.com. The book is also available to patrons of the Omaha Public Library.

One thought on “FBI Assistant Director William Sullivan rewarded with bonus after approving conspiracy against Black Panthers in Omaha”